Jacques Audiard’s genre-melding noir musical, Emilia Pérez, opens with a plea. Zoe Saldaña as Rita, a jaded defense attorney for white-collar criminals, is writing her closing argument, asking the jury to exonerate her client, a corrupt bureaucrat accused of pushing his wife off a balcony. But the following musical number, a grand procession through the streets of Mexico City, also functions as a plea to the viewer — to buy in, to accept the film’s idiosyncratic world, one where Rita quickly gets entangled with a drug lord (Karla Sofía Gascón) seeking gender-affirming surgery. “From day one, there was this understanding that if we didn’t manage to make that scene convincing,” says choreographer Damien Jalet, “we would lose the audience.”

Like the rest of the film, which “ranges from being a telenovela to a narco movie to a family drama,” says Audiard, the song — called “El Alegato,” which translates to plea — doesn’t fit cleanly into any category. It is both a rap and a power ballad, an orchestral anthem and a techno remix. “This fucker kills his wife,” Rita begins in an almost ominous whisper, typing at her desk, her face lit by a screen airing coverage of ongoing protests against femicide, “and we allege suicide.”

As she walks through a convenience store and back out onto the street, her breathy staccato takes on more intent. Her tone oscillating between bitterness and sincerity, she starts writing the speech that will ultimately free a man she knows is guilty. The tempo builds, and a bustling outdoor market emerges from the dark, dozens of dancers and market stands weaving around her, while a few self-contained scenes — including one blink-and-you-miss-it knife fight — play out in the margins. “What is it that we’re talking about today, right now?” she talk-sings, as a chorus begins to echo her words. “We’re talking about violence, about love, about death, about a country that is suffering.”

It is more than a closing argument. “It’s the birth of the movie,” says Clément Ducol, the song’s composer. And, tonally, it was important to set a standard. “We wanted to create a feeling in which the viewer can maybe start to think that daily life can be looked at through this lens,” he says. “Maybe a walk could be a dance; maybe the noise from a construction site could become a percussion orchestra.”

1.

Bring Mexico City to Paris

Photo: Page 114, Why Not Productions, Pathé Films, France 2 Cinêma

For the better part of a year leading up to production, Audiard and his team had planned to shoot on location in Mexico City. Then, in August 2022, when the start date got delayed several months, Audiard sent everyone an email saying he had changed his mind: He wanted to shoot in a studio in Paris instead.

Some of his concerns were practical. It was useful to not have to worry about background noise in musical numbers, for instance. “But what mattered most was that the studio gave me the opportunity to create some images that one cannot create the same way on location,” says Audiard, like a shot toward the end of “El Alegato” in which the chorus of voices from the crowd collapses into a moody piano melody and the world around Rita seems to go pitch black and freeze.

But re-creating the open-air market, known as a tianguis, posed some problems. The team scrambled to build one from the ground up, including dozens of market stands, which required specific design elements, like the 30 sets of string lights brought back from Mexico to achieve the right warm glow. Then there were the dancers: “I was like, ‘Okay, so Jacques, you need people in your market, and they should not look like tourists from France,’” says Jalet. Twelve Mexican dancers were flown in and reappear through the scene.

2.

Give Rita a Theme Song

Photo: Page 114, Why Not Productions, Pathé Films, France 2 Cinêma

Ducol and the French singer Camille first began working with Audiard in 2019, and from then until filming, the songs were in constant revision. Because the director was conceptualizing and writing the script simultaneously, adapting it from his original four-act operatic libretto, he would often raise an idea for a scene to Camille and Ducol and say, “Does that trigger a song in you?” The “Alegato” scene, though, was always going to be a musical number.

For the lyrics, Camille integrated the legal jargon that would typically go into a closing argument. She then used that as a template to introduce Rita’s inner conflict — she’s defending a man she knows is guilty, but she’s also keenly aware that corruption is a nationwide epidemic, undergirding every institution, and she feels helpless to stop it. “She’s denouncing corruption, and she’s corrupted,” says Camille. “Her singing is still meant to seduce a corrupted audience.” The lyrics swing from weary irony — “This case is a very mundane case / A case about violence” — to moments of chillingly resolute belief in her client. “Long live the triumph of love,” she sings about his professed devotion to his wife toward the end of the song. “Long live innocence.”

Spanish was its own challenge. Camille isn’t a native speaker, but “Jacques didn’t even ask me any questions,” she says. “He said, ‘Do you want to do the lyrics?’ and I said ‘yes.’ He didn’t ask me, ‘Are you sure you can write in Spanish? What level have you got? Don’t you want to take courses?’” She worked with Mexican language consultant Karla Avilez to root the song in its specific context, in northern Mexico where Rita is from, with the correct colloquialisms and accents.

3.

Let the Actors Move Their Way

Photo: Page 114, Why Not Productions, Pathé Films, France 2 Cinêma

Most films that involve dance include at least basic ideas or guidance for that element in the script, says Jalet, but Audiard’s had “absolutely nothing.” It was up to Jalet, who worked on Suspiria and with Madonna, to determine which songs even featured dance. The director also made it clear he didn’t want the look of a standard musical, pushing instead for intimate close-ups and Steadicam trailing during dance numbers and a modern, interpretive style of choreography. “At one point, I nearly left the film because I was like, ‘I don’t think you need me, guys,’” says Jalet.

Part of what kept him invested was Saldaña, who was trained classically as a dancer and has the skill to tell a story through movement. “El Alegato,” in particular, required intense care. The first three minutes, in which Rita merely types at her laptop, stops at a store, and enters the market, are “incredibly precisely choreographed, but you can’t tell because it’s just daily actions,” he says. Each word has a gesture attached to it, and something as simple as setting a cup down had to be intentional, timed to the second.

When, suddenly, the marketgoers surrounding Rita begin making beat-by-beat hand motions, it comes without warning, but it is here that the sequence hits its crest. While many of the moves seem intently descriptive — a finger across the throat for the phrase “slit throats” — they carry an underlying anger. The body language is harsh, angular, almost defensive: “an energy of resistance,” says Jalet. For Rita, there’s a wryness marking every motion. “It would not have been meaningful had I not added the sarcasm that Rita is feeling as she knows she’s lying,” says Saldaña. “In the dance, you really feel how disgusted, despondent, and detached she feels against this world that she has no control over.”

4.

Make It Look Like One Shot

Photo: Page 114, Why Not Productions, Pathé Films, France 2 Cinêma

“El Alegato” was the first scene they filmed once production got underway in April 2023. “I told myself that whenever you shoot a new movie, you have to start off with the most difficult part,” says Audiard. “So if you are shooting a western, you start with a gang fight. If you’re shooting a musical, you start with the piece that will require the greatest amount of energy.” They rented the biggest studio they could find in Paris solely for the sequence — everything else was shot on a different lot.

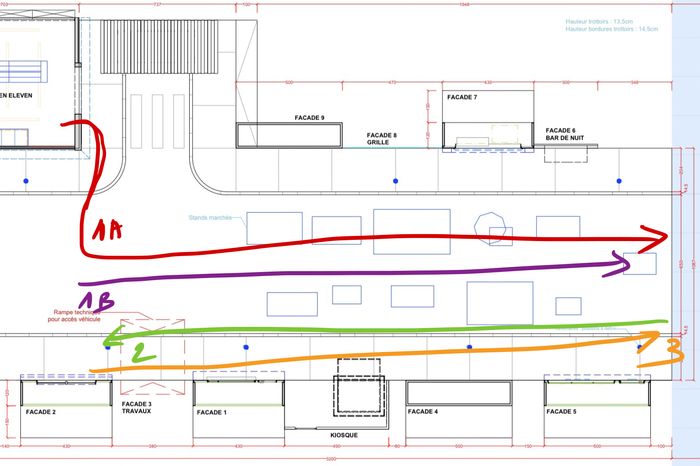

A couple of weeks before the shoot, Jalet began recording rehearsals in full with an iPad on a DGI stabilizer, establishing exactly when the remote-controlled market stands would shift in another direction or the camera would pivot to a different angle in order to make it seem like a different street and give the illusion of one continuous shot. Once on set, Jalet had to teach the Steadicam operator the same exact movements.

It was all in the service of preserving a kind of “chaos and roughness,” as cinematographer Paul Guilhaume calls it, which, counterintuitively, is sometimes harder than achieving a blockbuster polish. That’s why, he adds, the market stands are lit only with practical lights — meaning lights you can see in the shot itself, which start flashing then fade out as the song crescendos — and why, despite having two cameras on set, the resulting sequence mostly uses the Steadicam footage. “We are all very ambitious,” Audiard says. “And I could say pretentious, but let’s just stick with ambitious.”