The graphic novelist Emil Ferris wants to show me the first paintings she ever fell in love with. It’s early April, and we’re visiting the Art Institute of Chicago, a place that has outsize importance in Ferris’s work: The museum is a major character in her 2017 graphic novel, My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, a surprise critical and commercial hit. It’s also key to Ferris’s life. Her parents met as students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, formerly housed in the building. “I was probably conceived upstairs,” Ferris says, as she settles into a loaner wheelchair at the membership desk.

Ferris, who is 61 with an impressive head of wavy, graying hair, requires the chair today owing to lingering effects from a freak incident two decades ago. But she has had health issues all her life: Ferris was born with scoliosis severe enough that she couldn’t walk until the age of 2½. She once recalled “standing mostly nude in front of a group of doctors who pointed at my body and said, like, ‘See, now this is interesting.’” The experience, she added, “made me develop a sympathy for monsters.”

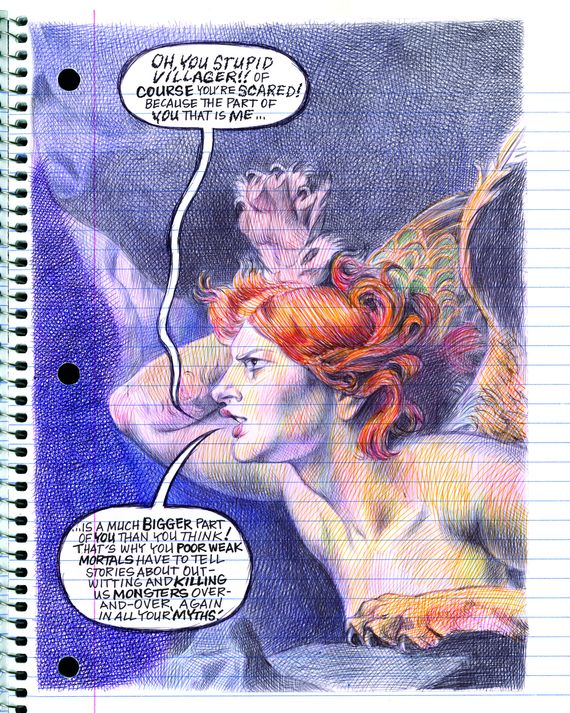

Ferris argues that the concept of monstrousness is “completely misunderstood.” She explains that there are three archetypes: the bad monster, the good monster, and the villager, the last of whom is motivated by fear and tends to reject those identified as different. “The vast majority of people don’t fit comfortably in any of those categories,” says Ferris, who speaks expansively and philosophically in measured, actorly tones (she pursued theater for a time). “I find myself in villager mode, I find myself in good-monster mode, I find myself in bad-monster mode.”

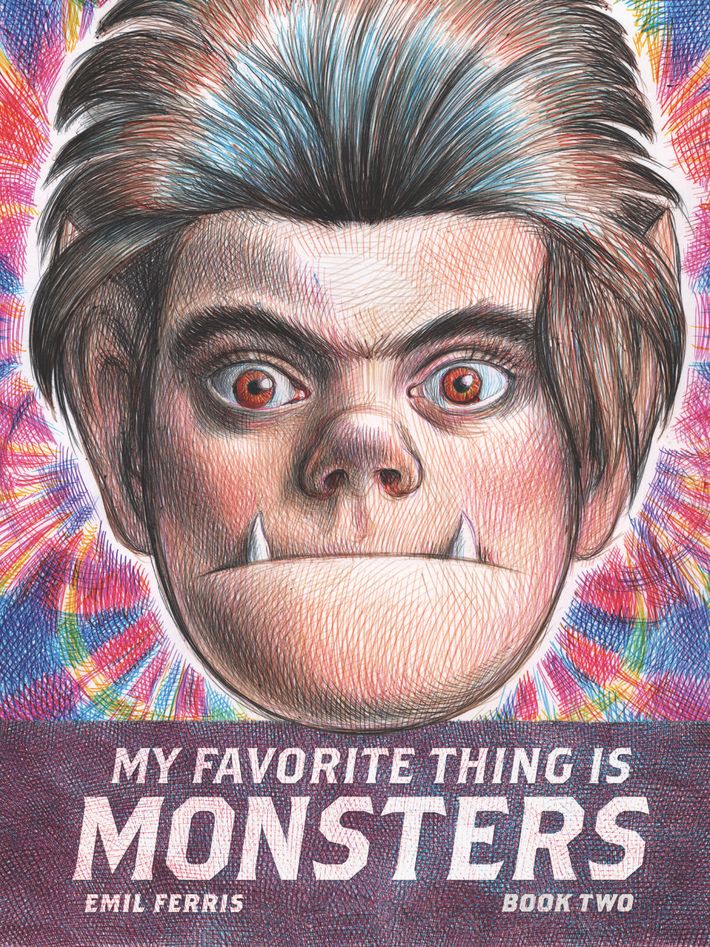

Illustration: Emil Ferris

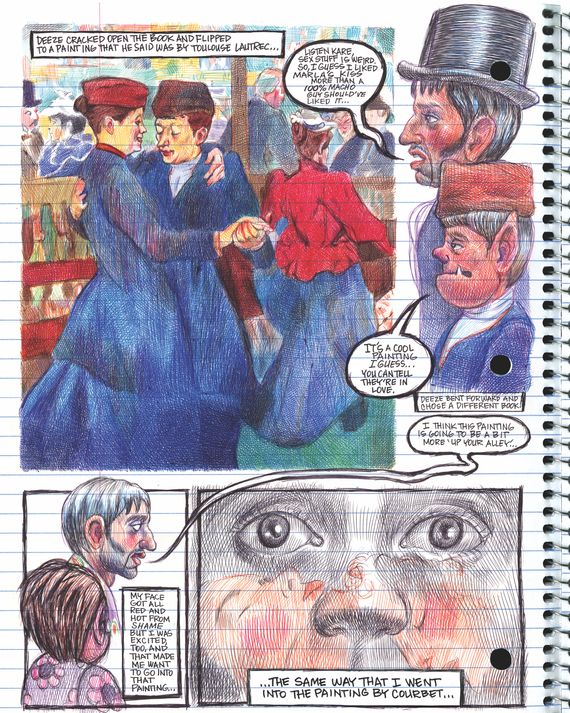

Set amid the turbulence of the late 1960s, My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is the lined sketchbook diary of Karen Reyes, a 10-year-old girl from Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood who portrays herself as a werewolf and yearns for “the bite” to transform her into an actual monster possessing eternal life. Drawn largely with ballpoint pen in an exquisite crosshatch style, the book is full of faux pulp-monster-magazine covers and re-creations of works from the Art Institute. Karen takes it upon herself to investigate who killed her haunted, gorgeous upstairs neighbor, the Holocaust survivor Anka Silverberg. Monsters is dense, deep, macabre, heartbreaking, and, quite often, very funny.

It was also an immediate success. The New York Times hailed Monsters as an “eerie masterpiece,” and Entertainment Weekly named it a top-ten book of the year. Ferris was on Fresh Air, an appearance she says she manifested. (“I talked to Terry Gross in my head almost every day while I was making the book.”) Art Spiegelman called Ferris “one of the most important comics artists of our time,” and Monsters won some of the industry’s most prestigious honors, including the Ignatz Award for Outstanding Graphic Novel and three Eisner Awards. To date, it has sold 100,000 copies, a phenomenal amount for a debut graphic novel. The equally brilliant book two, long delayed by a bitter dispute between Ferris and her publisher, arrives May 28.

The book has resonated particularly among older-than-usual graphic-novel readers, many of whom Ferris says have felt inspired by her as a late-in-life first-time author. Ferris, who is not religious but believes in the mystical, describes a vision she had in her studio in which a giant funnel appeared above her head. “People were beginning to look down into it, to try to come into it, because they were reading the book,” she says. “Karen’s world now lives in hundreds of thousands of people.”

Monsters is about identity and otherness: Karen is poor, mixed-race, queer. In My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Book Two, Karen gets a girlfriend, whom she meets in a bathroom at — where else? — the Art Institute. “She’s me, but she’s also not me,” Ferris, who is bisexual, says of her young protagonist. Like Karen, Ferris grew up longing for the bite that would turn her into a bona fide monster. “Do you want to spread your wings and fly up in the sky at night?” Ferris asks. “Wouldn’t you want that? I would.”

Ferris takes me to an uncrowded gallery on the museum’s second floor to see a series of paintings by the 15th-century Italian artist Giovanni di Paolo. They depict the life and death of Saint John the Baptist, except two of the six works are not currently on display, notably the one in which Saint John is beheaded, blood spurting dramatically from his neck stump. “The truth is told in this brutal moment,” she says, chagrined by the painting’s absence.

The absent di Paolo reminds her of growing up poor in the 1960s in Uptown, a multiracial, “incredibly violent” neighborhood where she once witnessed a young friend accidentally get beheaded while “skitching” — grabbing the back fender of a car and surfing the snowy road. On another occasion, she saw the body of someone who had fallen out of an apartment window. Meanwhile, a serial killer abducted a local babysitter. “So many children died,” she says. “I didn’t put it in the book. It was too much. I made a much nicer Uptown than it actually was.”

Ferris was born off Stony Island on Chicago’s South Side. Her mother, Eleanor Spiess-Ferris, is a surrealist painter descended from early Spanish settlers and Indigenous Mexican peoples in what became New Mexico; her father, the late Mike Ferris, was the child of Lebanese immigrants and a toy designer. The Ferrises spent time living in New Mexico before moving to Uptown in 1966. A few years later — after Mike got a job at a toy-design company, where he would go on to create the classic Mickey Mouse rotary phone — the family was able to relocate to nearby Rogers Park. It was there that Emil, who is part Jewish, heard the stories of Holocaust survivors firsthand. (Emil now lives in Evanston, just outside the city.)

A fan of Mad magazine, EC Comics, and creature features, Ferris fell in love with cartooning early on. As a kid, she had sharp canine teeth that a dentist sawed down against her wishes; she was also hirsute, though not so much anymore. She pulls up her sleeve to show a smooth forearm. “I’m an old, balding werewolf now,” she says with a laugh.

At age 10, she had surgery to correct her spine’s curvature, spending the next 11 months in an upper-body cast. A weird kid, she loved that the neck part resembled a Tudor doublet. By 16, she had dropped out of high school; she ran away from home and slept in parks for six weeks before getting her own apartment. As an adult, she worked various jobs to make ends meet, including a stint as a house cleaner and as a freelance magazine illustrator.

When she was 34, she gave birth to a daughter, Ruby, and raised her solo. Ferris would rather not reveal the identity of the “very, very handsome” father, whom she got together with after an eight-year relationship with a woman. “I decided to try on an experience with a man, and it gave me a daughter,” she says. “Ultimately, that was what I wanted.”

At her 40th birthday party, a twisted version of Ferris’s wish for “the bite” came true — she was bitten by a mosquito and contracted West Nile Virus. “After the party, I remember the feeling of electricity going through my whole body,” she says. One week later, she was hospitalized. Ferris found herself once again immobilized, paralyzed from the waist down. Even worse, in her mind, her drawing hand didn’t work.

“I had the vision of this big rock floating in front of my head,” she says of her time in the hospital. “And I heard this voice that said, ‘All the gold is inside the rock, you’re gonna have to chip away.’” And she did: Thanks to intensive physical therapy and assistance from her mother and daughter, Ferris began to draw again after a number of months, initially with a pen duct-taped to her hand. She eventually enrolled in B.F.A. then M.F.A. programs at the School of the Art Institute. She likes to point out that she began college in a wheelchair and graduated walking with two canes. (Today, she’s down to a single snaky wooden cane.) “It’s just a miracle that I can walk,” she says.

At school, she was inspired by Spiegelman’s Maus to make her own graphic novel. Ferris had more than a dozen ideas for projects and enlisted Ruby, at that point a teen, to help her choose. “She said, ‘It’s My Favorite Thing Is Monsters. That’s the biggest world you can build.’” The graphic novel was based on a short story she wrote in 2004; nearly ten years later, she completed the initial Monsters manuscript. By then, she was in her early 50s.

Only after the book was published did it become clear to her why it took her so long to return to her childhood passion of cartooning. In the 2019 comics anthology Drawing Power: Women’s Stories of Sexual Violence, Harassment, and Survival, Ferris revealed that while visiting relatives as a young girl, she found herself alone with a person who had repeatedly subjected her “to sly, sexually oriented brutalities.” At the time, she was watching a Mr. Magoo special on TV, befouling her relationship with cartoons.

“It’s almost impossible if you’re female” to avoid such experiences, she says when I ask her about the incident, which occurred when she was 8. “Unless they were very sheltered or fortunate.” Not surprisingly, sexual violence, or the threat thereof, permeates Monsters. In book two, Karen comes to a realization — introduced in a way that’s easy to miss — about her recently departed mother. “This icon of female strength to Karen was sexually brutalized,” Ferris says. “And she knows this on some level.”

Monsters was eventually picked up by Other Press. When that deal fell through, Ferris’s agent submitted it to Seattle-based comics publisher Fantagraphics, which accepted it immediately. “I was convinced that ‘Emil Ferris’ was a pseudonym for someone who’d had a long professional comics or illustration career,” says Fantagraphics’ Eric Reynolds, who edited book two. “Because I just couldn’t believe that something so fully formed could come out of nowhere.”

The new publisher decided to divide the book, then totaling more than 600 pages, into two parts. Fantagraphics co-founder Gary Groth edited the first 400-page book, which he describes as a fairly smooth process. The main complication came about later, when the cargo ship carrying the original print run stalled in the middle of the Pacific Ocean for nearly a month because the vessel owner was bankrupt. Since the shipper couldn’t pay the requisite fees once the ship reached the Panama Canal, the Panamanian government seized the vessel. The ship was eventually released, and the Halloween 2016 release date was pushed back to Valentine’s Day 2017.

No one involved in Monsters’s publication is exactly sure why the book became so successful. Groth suspects part of the interest in it had to do with Ferris’s backstory — the press homed in on her paralysis from West Nile — and the novelty of the book getting lost at sea. Ferris theorizes that she was the beneficiary of “mass guilt” in the comics world; her book came out the year after cartoonist Daniel Clowes and others boycotted comics’ Grand Prix d’Angoulême, a lifetime achievement prize, because there were no women nominees.

Book two was slated to be released in July 2017, but sticking points emerged. According to a lawsuit Fantagraphics filed against Ferris in June 2021 — the only time the publishing house has sued an author in its 48-year-history — she told Fantagraphics early on that she wanted to “polish” the second volume, but that process dragged on. Ferris “blamed her failure to deliver the promised version on her mental and/or physical health, on a defective computer, and on her claimed need to generate other income,” the suit reads. “But lately, for the first time, mostly through her newly-acquired lawyers, she has claimed that Fantagraphics does not even have the right to publish Book 2.”

At issue was whether the second volume was a continuation of book one or a sequel, and if the “remnants” not included in the first book automatically qualified as part of the second book. In addition, the artist’s attorneys claimed in response to the suit, she felt “bullied” by her publisher and “suspected that Fantagraphics was lying to her and underpaying her.” After Ferris called for an audit, she alleges Fantagraphics “stalled and stonewalled” before deciding to sue. The parties reached a provisional settlement in September 2022; the suit was dismissed six months later, after Ferris delivered her completed manuscript.

Both sides agreed not to discuss the particulars of their legal fight. “That kind of situation can threaten your desire and your engagement with the world you’ve created,” she says of the lawsuit. Promoting the second book together, even though she will no longer be working with Fantagraphics in the future, feels like going through “a divorce,” she adds.

Ferris has since taken up with a new partner, Pantheon, for which she’s creating a Monsters prequel, Records of the Damned, and an illustrated noir called A. Rosenbloom and the Marionette Murders, “about a puppeteer who survives the Holocaust.” (That’s in addition to five other ongoing projects, including an autobiographical novel. Ferris, meanwhile, is in talks regarding a live-action Monsters movie.)

In February, the New Yorker published the first excerpt from Book Two. (The volume was delayed one last time, when China’s press agency objected to a few pages, forcing Fantagraphics to scramble to print it in Malaysia.) In part two, Karen gets to the bottom of the books’ central mystery, discovering some more dark secrets about her family along the way. Meanwhile, the portrayal of Anka’s experience in a Nazi concentration camp, told when Karen hears Anka’s recorded testimony, is even more harrowing than in the first book. Still, Ferris is not fully satisfied with the end result: “I swear to God, if I could have my way, the book would be something you could lay on people and it would cure their stomach cancer.”

I wonder how Ferris thinks the new book will be received. “I don’t know,” she replies. “I’m doing this with you right now —” She pauses. “I’m not doing it because the book will make more money. I’m doing it because I thought maybe I met you in a past life.” (Perhaps on the plains of Ukraine or Poland, she says. Maybe one of us saved the other, or we might have killed each other. She just knows that she wanted to meet me in this life.) “It’s never about the money,” Ferris continues. “The money is the excuse we give so that we can sink our teeth into the life” — in her case, the life of an artist.

Ferris doesn’t want “the bite” anymore. “I’m too old to carry that off,” she says. “There’s a lot of loping in the forest. There’s howling at the moon, which I did once, and afterwards I was coughing for like half an hour.” Ferris would prefer to be an “old witch,” one with no intention of eating the children drawn to her candy house. “She just wants to take them under her wing, teach them some baking tips, and tell them stories,” Ferris says. Bite or no bite, she’d still love to fly up in the sky at night. “It just takes a broom now,” Ferris says with a laugh. “I can’t do it without the broom.”