This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Griffin Dunne is at ease with himself in the way that people who have always been good-looking usually are. Even at 68, his salt-and-pepper hair is thick enough to be pushed back, and he comes across as whatever the opposite of tightly wound is. When we meet for lunch at Cafe Mogador, around the corner from his apartment in the East Village, I can still see a trace of the hapless Paul Hackett he played in After Hours, the 1985 Martin Scorsese movie about a night out in Soho that goes spectacularly sideways. It’s clear from reading Dunne’s new memoir, The Friday Afternoon Club, that he is quite familiar with life going sideways.

Dunne has had an interestingly windy career. He’s been an actor in movies — he co-starred with Madonna in Who’s That Girl in 1987 and tells a funny story about the not-so-tame mountain-lion extra in the film — and on TV, most recently in The Girls on the Bus, playing a newspaper journalist loosely based on David Carr. He directed films including 1998’s Practical Magic and The Center Will Not Hold, the 2017 Netflix documentary about his aunt Joan Didion. Which brings us back to the real subject of his book: not his career but his messy, tragic, famous, feuding Hollywood-Irish family.

“We were clinically crazy,” he says, taking a bite of his tuna niçoise salad. “Like, really crazy.”

He grew up in Beverly Hills at 714 Walden Drive, surrounded by movie stars. Sean Connery saved him from drowning in the family swimming pool. Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, and Roman Polanski all hit on his girlfriend at the same time (“Like three wolves sniffing a baby lamb,” he says). He took Carrie Fisher’s virginity and smoked pot with Harrison Ford when Ford was just his Aunt Joan’s carpenter.

Griffin’s father, Dominick Dunne, was a movie producer who washed out and then reinvented himself after writing in Vanity Fair about the 1983 murder trial of his own daughter — a starlet, in that era’s language — named Dominique. (She was Griffin’s little sister; The Friday Afternoon Club is named for a party she used to throw for her acting class.) That magazine article launched Dominick’s second act as a high-flying chronicler of high-society crimes — a true celebrity journalist of a type we don’t really see anymore. He would go on to cover the trials of Claus von Bülow, O. J. Simpson, the Menendez brothers, and Phil Spector. Dominick’s brother, the writer John Gregory Dunne, was married to Didion.

But now Didion and both brothers Dunne are dead and gone, which leaves Griffin free to tell his version of their stories. His book details his father’s closeted sex life (Dominick never publicly acknowledged being gay) and his envy of John’s and Joan’s literary success. Griffin also writes candidly about how uncomfortable he has always been with the fact that his sister’s strangulation is what finally allowed his father to attain the personal fame he’d long craved.

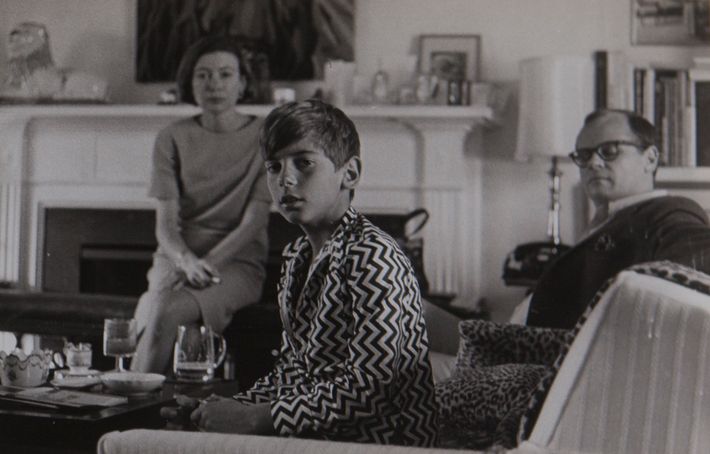

Photo: Courtesy of Griffin Dunne

The memoir basically begins in West Hartford, Connecticut, where his father grew up wealthy, one of six children of a heart surgeon but still an outsider to Wasp society. “Even lace-curtain Irish were not allowed in the blue-blooded country clubs,” Griffin tells me at lunch. That striving for status drove his father his whole life. Years later, Dominick would make his children pose for Christmas cards in the style of British gentry: “I once referred to it as him basing it on Cecil Beaton’s photographs, and he went, ‘No, Griffin. Lord Snowdon. Get it right.’”

After winning a Bronze Star fighting the Nazis, Dominick married Ellen “Lenny” Griffin, a well-to-do Arizona girl who had moved east to go to Miss Porter’s, an all-girls boarding school in Connecticut. He got a job working on The Howdy Doody Show. In 1957, the family, which by then included Griffin and his brother, Alex, moved to Los Angeles, where Dominique was born. Dominick became executive producer on a series called Adventures in Paradise. He went on to produce films including The Boys in the Band (1970), The Panic in Needle Park (1971), and Play It As It Lays (1972) — the last two were written by John and Joan.

Joan was already well known by the time John introduced her to Dominick and his children in 1963. She stirred up Dominick’s insecurities from the start. “A novelist living in Los Angeles was then a novelty, and my parents showed more attention to the details of this lunch than they ever had entertaining Hedda Hopper or an out-of-town viscount,” Griffin writes. “Dad made Alex and me change outfits several times before deciding we’d look most impressive in matching red swim trunks, each with a gold buckle.” But when he got out of the pool to introduce himself, one of his balls was hanging out of his trunks. “She was the only one who did not laugh, just held eye contact with me,” which, he says, encapsulated her style as a writer “of not joining the crowd, of looking at something differently. She saw a little boy being humiliated.”

As Didion’s reputation grew, Dominick soon began to be known foremost as “Joan Didion’s brother-in-law” — which, given Dominick’s thirst for fame, he did not like. In 1965, just before Griffin’s 10th birthday, his parents split up. “The parties and name-dropping had grown tiresome,” Griffin writes, “and even Mom’s closest friends found the pluck to ask why on earth she stayed with him.”

There was also the fact that his father was quite obviously gay. He had two poodles with shaved chests and pom-pom tails named Oscar, as in Wilde, and Bosie, which was Wilde’s nickname for the lover who brought scandal on him, Lord Alfred Douglas. Griffin just wanted a German shepherd. “My fragile identity at that time was tied to a father who couldn’t throw to third and gave me two French poodles named after famous homosexuals,” he writes a tad ashamedly.

He also writes in the book that he grew up wishing his father “could have been more like his tough Irish younger brother … Uncle John was one of the first journalists to report from Vietnam. He and David Halberstam whored around the Saigon Hilton and flew in country on Hueys while embedded with the Army. He started fistfights with competing reporters in Manhattan watering holes and walked the streets of Watts during the height of the riots for Life magazine.”

On a family vacation to Hawaii one year, Dominick brought his friend Don. Griffin later realizes that “handsome, athletic, funny Don was doing my dad.” Griffin writes about making a move on Torey, a young actor who lived at his father’s house and worked as a “valet.” They dropped acid — there is almost as much acid as there are names dropped in this book — and jumped into bed together until, Griffin writes, “Torey kicked me out of bed, not unkindly, after I’d let him do stuff to me and I’d done stuff to him, all to no great effect.” Yup, definitely straight!

In 1972, his father flamed out of Hollywood. One night, while he was in the middle of making Ash Wednesday for Paramount (starring Elizabeth Taylor), he drank too much at dinner and made a fat joke about the most powerful agent in town, Sue Mengers. He did this in front of a reporter for one of the Hollywood trades, who printed the remark the next day. A Paramount exec called Dominick and told him his career was over. Sure enough, his phone stopped ringing.

Drunk, alone, blackballed, and broke, Dominick spent the rest of the decade spiraling. The book describes the moment he was evicted from his apartment on South Spalding Drive, how he had to sell his Mercedes and buy a used Ford Granada, and how Dominique came over to help him hold a yard sale. “People he once entertained, who’d long since dropped him, heard of his misfortune and showed up to haggle and pick through his treasures,” Griffin writes. His father ended up in a little town in Oregon — he was driving through when his car broke down, and he stayed — where he started going to A.A. meetings.

Living in a cabin there, he wrote a trashy Hollywood novel, The Winners, which came out in 1982. (He went on to write many other gossipy novels set among the rich, including The Two Mrs. Grenvilles and An Inconvenient Woman.) His friend Truman Capote wrote him and said, “This is not where you belong. When you get out of it what you went there to get, you have to come back.” Buoyed, Dominick moved to Manhattan and rented a studio apartment in the Village.

Griffin was living in New York, too, trying to become an actor. He and Fisher became roommates in the Hotel des Artistes on West 67th Street. One day, he writes, “Carrie said offhandedly that she had landed a job in some science-fiction movie shooting in England.” He asked if she could get him a part, but the other lead had just gone to … that carpenter he’d once shared a joint with who had built John and Joan’s deck. And besides, Fisher thought the movie was going to be “a fucking disaster.” As she had told him, “I’m acting with an eight-foot yeti and a four-foot Brit in a rolling trash can!”

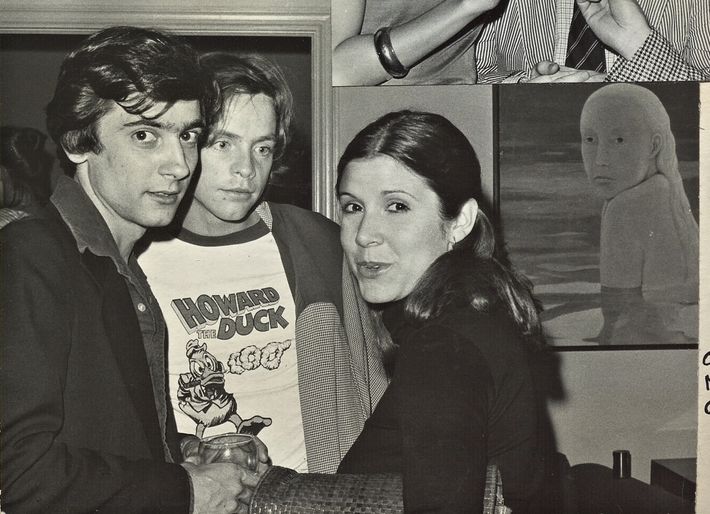

Photo: Courtest of the McGrath Estate

In 1981, he starred in An American Werewolf in London, and things were going well. Dominique was living in L.A. and also acting. She got her first big role in Poltergeist playing the sister who hops out of the Trans Am and screams “What’s happening?!” She had also started dating John Sweeney, the hulking sous-chef at a trendy L.A. spot (the number was unlisted) called Ma Maison.

The family felt there was something off about him, but the only one to speak up was brother Alex. Sweeney eventually beat up on Dominique, who broke it off with him. Griffin, then 27, warned Sweeney to “stay the fuck away from her.” On October 30, 1982, when Dominique was 22, Sweeney turned up at her house at 8723 Rangely Avenue holding a bag of freshly baked Halloween cookies, begging to be taken back. “Ten minutes later,” Griffin writes, “his hands were around her throat.”

The book recounts the family seeing her for the first time in the hospital, “a swollen creature” hooked up to a breathing tube, head shaved with “bolts boring into her skull … eyeballs bulged like a cartoon character who’d put her finger in a light socket.” Told she would never recover, the family took her off life support five days after the attack.

A media circus ensued. The trial began in the summer of 1983. The defense played rough, smearing Dominique as a promiscuous party girl who had it coming. According to the book, Dominick was also wound up by the fact that the newspapers referred to his dead daughter as “John Dunne and Joan Didion’s niece.” And then he had to find out through an intermediary that his brother and sister-in-law were fleeing the country for the entirety of the trial. Their troubled daughter, Quintana Roo, had socialized with Dominique, and the notable couple worried she might get dragged onto the stand, so they took her to Paris. Dominick was devastated and enraged. “Quintana was a wild child,” Griffin tells me. “John, who’d walked the halls of that courthouse and knew the cops and DAs, saw where this was going. They left to protect their daughter, but that didn’t mean we didn’t feel betrayed.”

“My father’s madness came out in a rage toward his brother that goes back from the time he became successful,” says Griffin. “There was so much resentment there.” He adds that when he made his documentary about Didion, “we did talk about the trial, and I decided not to leave it in. ‘Where did you go? Why didn’t you go?’ She explained it to me. It didn’t fit in the doc. It was, by the way, incredibly uncomfortable for both of us to have to talk about that so many years later.”

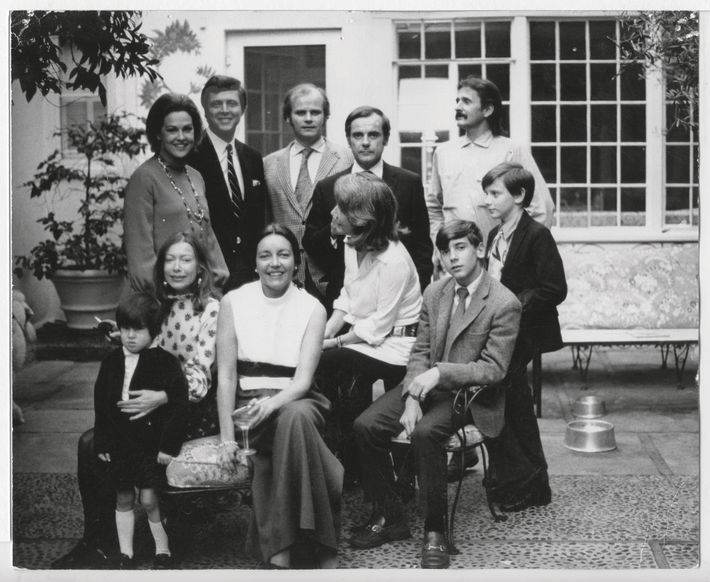

Photo: Courtesy of the McGrath Estate

Before the trial had started, Dominick had been invited to dinner by his journalist friend Marie Brenner. There, he met Tina Brown, the young editor from London who would soon take over Vanity Fair. In her own 2017 memoir, Brown recalled that dinner and how Dominick vented about the upcoming trial: “Marie told him he should think about keeping a diary … I said if he did, it’s something I’d love to publish in Vanity Fair. His face lit up as if I’d just thrown him a lifeline.” (Brown wrote of a lunch at La Goulue later on, at which Dominick talked about “how his sister-in-law Joan Didion was closing a piece for the New York Review of Books and wouldn’t get off the phone when they needed to communicate with the cops.”)

In the end, Sweeney was sentenced to only six and a half years in prison, of which he served just three years and seven months. Dominick’s story about the ordeal, “Justice: A Father’s Account of the Trial of His Daughter’s Killer,” gave him a new life. At the time it came out, John and Joan were back living in Manhattan but not on speaking terms with Dominick. Griffin made an uneasy peace with his aunt and uncle, but all three knew better than to discuss the trial. “I was Switzerland, and I made terrible attempts to pacify the situation,” he says. “Joan was really caught in the middle as well. That’s another thing we sort of had in common. We would just look without ever having to say, like, ‘Oh, these fucking Irish guys. Jesus Christ.’” He would meet them for dinner at Elio’s on the Upper East Side, and, as he writes, “Dad would call the next morning to say, ‘I hear you were seen with John last night,’ as if I were a Nazi collaborator.”

After Dominick’s article about the trial was published, his own star began to rise, which added a new element to the grudge. John had been known for his crime reporting, and suddenly Dominick was surpassing him to become the best-known crime reporter in the country. “My father’s success in John and Joan’s domain was another subject left unspoken during our dinners at Elio’s,” Griffin writes.

Not that he was entirely thrilled for his father either. “I wasn’t crazy about the article when it came out,” he says. “I was too close to it, and it seemed too personal.” He writes about how he would “audibly groan” seeing his father ham it up “on the countless talk shows where he was now a fixture. His addiction to alcohol had been replaced by a craving for publicity, granting interviews to anyone from even the lowliest rags.” He eventually came to appreciate all that his father had communicated in the magazine story. “The article itself became a template of who I am,” he says. “If I met someone who was going to be, I felt, significant in my life, I said, ‘You should read this to understand me, a user’s guide.’”

Irish Alzheimer’s is when you forget everything but the grudges. Miraculously, at the end of their lives, Griffin’s father and uncle were able to overcome theirs. John, who had suffered a heart attack, went to see his doctor and bumped into his brother in the waiting room. Turned out they shared the same cardiologist. Dominick took a seat across the room and pretended to read a magazine until his brother spoke up, asking, “When was yours?” They struck up a conversation until the nurse called out, “Mr. Dunne, the doctor will see you now.” To which they both replied, “Which Dunne?” Ever after, they talked on the phone each day until the one in late 2003 when John dropped dead of a heart attack at his dining-room table. The first person Joan called was Dominick. (He died in 2009; she lived until 2021.)

“I always knew that the resolution would be the incredible thing of them sharing the same coronary doctor, then going, What the fuck are we doing?” says Griffin. “It’s so happy. Dad, he would say so many times, ‘Thank God I walked into that office.’”